Filter

My Wish List

![]() Zoanthus Coral Care

Zoanthus Coral Care

![]() Taxonomy

Taxonomy

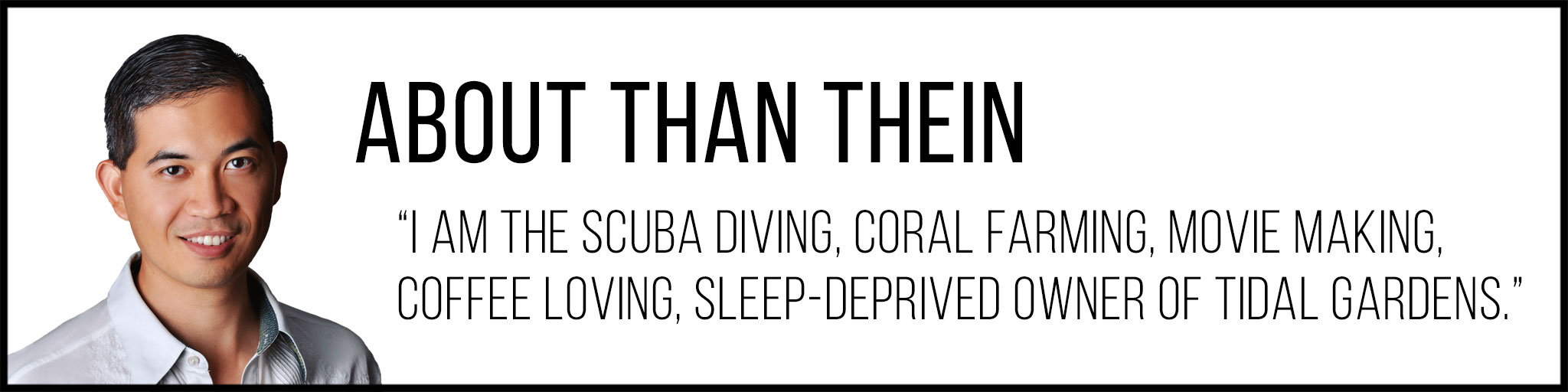

Zoanthus are a genus of corals within the order Zoantharia, an order it shares with Palythoa and Parazoanthus. You may have also heard zoanthus referred to as zoanthids which is correct, but if you want to be a stickler for details, the term zoanthids refers to all the corals in the order while zoanthus is specific to the genus.

As a practical matter, there is some degree of fogginess you will encounter in this industry whether something is called a zoanthus or a palythoa because there is a wide range of physical variation within the genus. There are some corals that are easy to place, for example Zoanthus sansibaricus or Zoanthus sociatus. They are the very small polyp zoas such as industry favorites Rastas, Blue Hornets, Fruit Loops. Clearly zoas.

Palythoa Grandis

On the other end of the spectrum you have the colossal Palythoa grandis that can sometimes develop polyps that are 2” in diameter and look completely different. Once again, not a ton of debate to what is what.

Things get a little murkier at the fringe of very large zoas and very small palythoa such as the purple death and nuclear green color variants that are in some cases smaller than a zoa. At that point, those larger zoas sometimes get lumped in with palythoa. For example, you might see Magicians or Utter Chaos listed as either. It’s not really much of a scientific distinction, it is purely a naming convention that exists in the hobby. Even we do it on occasion because we want people to find what they are looking for and in this case it is easier to meet people where they are.

There are some other differentiators between the two such as palythoa’s propensity to incorporate substrate into its flesh, something zoanthus does not do. There are also differences in the tentacles and the growth of the mat. Also there are genetic differences, but that is cutting edge stuff and not nearly as straight forward as it may seem. There is a LOT of genetic consistency so it is a chore to find small segments of DNA that are actually different enough to base a scientific classification on.

Over 90% of the coral’s genome is identical so a lot of current research is delving into that. Genetic research is further complicated by the effect the environment has on the expression of the genetic code. The genes themselves don’t change but the how the organism reads the genetic code in response to the environment does so you could see two very different traits in corals originate from an identical genetic sequence. If you want to go down that rabbit hole do a search on epigenetics and DNA methylation.

That is as deep as I am going to go into taxonomy. It is a constantly evolving field and you can expect reclassification over time as more research is done.

![]() Palytoxin

Palytoxin

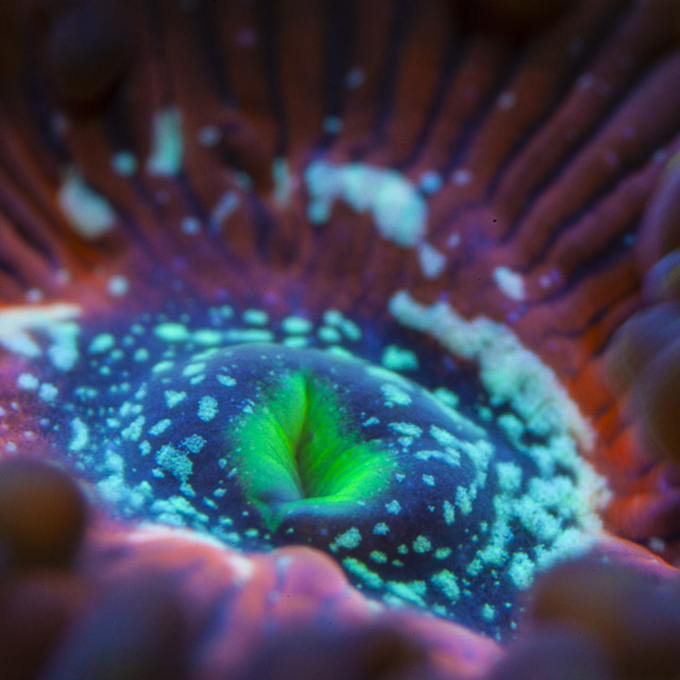

Before we get into the care tips for zoas, I need to address the potential toxicity of these corals. Some can contain a compound called palytoxin that is a very dangerous poison. Palytoxin is associated more with Palythoa than Zoanthus, but it is possible for zoas to have it. I don’t know if those zoas produce it themselves or acquire it from neighboring Palythoa. In the wild, palytoxin shows up in organisms that don’t actively produce it such as sponges, mussels, and starfish but live in close proximity to palythoa. It can even be found in other species up the food chain such as crabs and fish through biomagnification. I’ll touch on this again when we discuss pests, because as lethal as palytoxin is, there is no shortage of organisms that are more than happy to consume them with no ill effects.

The scientific community has been aware of palytoxin since the 1960’s but it has been used as a means of biological warfare by Polynesian cultures for much longer. There is a legend of a sacred seaweed that grew in a special pool that when applied to a warrior’s spear would bring sure death to his enemies. In 1961 researchers tracked down the fabled pool in Maui and found colonies of Palythoa toxica.

Magician Zoanthid

It wasn’t until the 1990’s that the mechanism of action was identified. Palytoxin binds to the sodium potassium pump on the membrane of cells. If you don’t remember what this is from high school biology, the sodium potassium pump is REALLY important to ion movement in and out of the cell and affects all sorts of biological processes so any interruption of that royally screws things up. It is why the symptoms of palytoxin poisoning are seemingly all-inclusive. Initially there was some skepticism regarding this mechanism of action but it was confirmed in 1995 in a pretty clever study. They exposed yeast cells to palytoxin because yeast cells don’t have a sodium potassium pump. Those yeast cells were unaffected but when given to yeast cells that researchers genetically modified to encode a sheep’s sodium potassium pump, all the cells died.

In practice you are not likely to get palytoxin poisoning just by having zoas or palythoa in your home aquarium. It resides in the flesh of the coral so it becomes an issue when the colony is damaged. People have gotten sick from scrubbing palythoa off of rocks or propagating a colony with a band saw that would send the particles airborne and then inhaled. People have also gotten sick by boiling rocks with colonies on it because that too sends the compounds airborne and unlike many other proteins, palytoxin does not lose its toxicity when heated.

I don’t think anyone has ever tried eating zoas, but I am guessing that would be a really really bad idea. Actually… don’t eat anything from your aquarium because THEY eat a lot of stuff and can become super toxic. One super deadly toxin is even named after a tang (Maito-toxin), THIS ONE that I’ve had in my tanks forever because it eats toxic dinoflagellate. I never was worried about poisoning because I never considered eating him! I don’t know why I need to say this, but people do stupid stuff all the time. Don’t eat stuff from your tank. This isn’t red lobster.

If you are concerned about the toxicity associated with zoas, take precautions handling them or avoiding them altogether. There are plenty of other corals in the hobby to enjoy… Having said all that zoas are one of the most popular corals in the hobby spanning decades.

If you are a hobbyist that can’t get enough variety, zoas have you covered. They are arguably one of the most diverse corals with hundreds of color morphs and patterns. At any given time we are farming over a hundred different varieties of zoas but looking back at our catalogue of photos that extends back 20+ years there are probably a hundred different variants we’ve had over the years that we either sold out of or lost and are nowhere to be found anywhere in the industry. Additionally, there always seems to be an influx of new brightly colored variants popping up in the hobby every year. If you are the type that just loves to collect every variant of a coral, the zoanthus Pokemon catalogue is extensive.

![]() Location

Location

Zoanthus and Palythoa are found in corals reefs around the world. However, most polyps in the reef keeping industry are harvested mainly from the islands of the Indopacific, including Fiji, Tonga, Solomon Islands, and the Great Barrier Reef.

Now that we have gone over some of the background of this coral, let’s get into the care requirements.

![]() Lighting

Lighting

Zoanthus are photosynthetic corals. Residing in their flesh are a symbiotic dinoflagellate called zooxanthellae that carries out photosynthesis. Zooxanthellae utilize chlorophyll to absorb light, the byproduct of which are simple sugars that the Zoas can consume for energy. Some corals rely on this energy source more than others and will need brighter lighting. On the other end of the spectrum, a coral that is receiving too much light may expel zooxanthellae from its mouth to regulate the how much energy is being produced. If you ever see a coral expelling what looks like brown slime it is likely attempting to regulate zooxanthellae concentration.

Zoas can be grown successfully in a wide range of lighting conditions. We have successfully grown Zoas in both bright and dim light conditions. They are very adaptable in that regard.

On average we have them in tanks with PAR in the 75-125 range however I have personally seen them on the reefs in Vietnam under about 6’ of water and the PAR there might have been well over 2000. In a home aquarium I don’t recommend going anywhere near that bright because there are a lot of things about life in the ocean that does not translate to home aquariums and 2000 PAR lighting would be one of them.

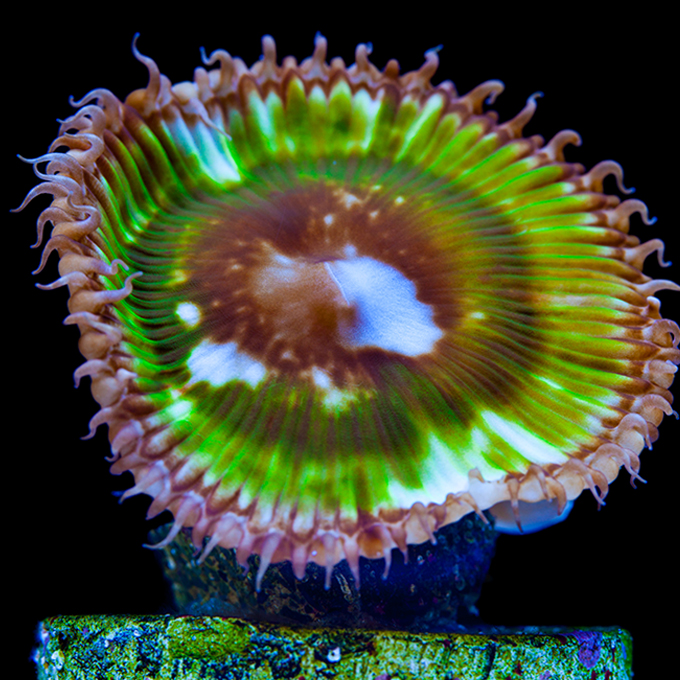

Although these corals will happily adapt to nearly any lighting regimen, you can expect some differences in appearance depending on both spectrum and intensity.

First let’s talk about their color. It is possible for some color morphs to develop intense fluorescent coloration under brighter lighting. If you have a colony that appears drab, increasing light may help. Remember that lighting that is too bright risks damaging the coral, and this damage can happen quickly. If you start to see the coral starting to turn lighter and bleach out, it is time to move it to a dimmer location. If you want to experiment with higher lighting intensities, do so very slowly.

The spectrum of light also will play a major role in the appearance of the polyp. Some zoas are very fluorescent and will display their most vivid colors under pure actinic lighting. Others that have less fluorescence will look much better under daylight lighting and might look completely muted in heavy blue light.

Next, let’s talk about how lighting effects their shape. In lower intensity light around 50 PAR or less Zoa polyps extend towards the light. In more intense light the stalks shorten and the colony takes on a flat mat-like appearance.

Light may also influence the size of the polyp. There are likely more impactful variables, but Zoa polyps can triple or quadruple in size depending on how happy they are with the tank’s parameters.

Low Light

Lighting is a loaded topic, so for a more in-depth discussion of lighting, please see our Deep Dive article.

![]() Flow

Flow

One such parameter that might influence their appearance more than light is the flow provided. If there was one parameter that I would obsess over with regard to the care of zoas it would be water flow. We have sold zoas to local hobbyists and purchase them back years later. One time I remember getting a colony of radioactive dragon eyes back and the size of each polyp was monstrous. I think this was due in large part to where they were located in his tank and how much flow the colony received.

Zoanthus by their very shape invite detritus accumulation and a colony that is dirty is very different than one that is kept clean. The buildup of detritus can slow a colony’s growth or even cause it to die back. Strong water flow helps keep detritus buildup to a minimum, as well as flushing away waste that the colony generates

When designing flow patterns for this coral I like to provide strong consistent flow with short bursts of very strong flow. If you do not have controllable pumps to achieve this it can be done manually with a turkey baster. Once a day you can squirt water at the colony to dislodge any buildup. I use just enough force to close the polyps up.

Electric Oompa Loompa Zoanthids

If you decide to go this route only do this with established colonies that are well attached. If you have a freshly glued Frag of zoas they might get blown away.

![]() Placement

Placement

In the case of my friend that grew this massive colony of zoas, he had it growing nearly vertically on his overflow box and had flow directed across the colony. The vertical orientation and the flow from both the pumps as well as the overflow itself made detritus settling nearly impossible.

This is an extreme example, but the principles remain the same. You want to keep the coral in a place that it can stay clean. Zoas unlike Palythoa do not like substrate. Palythoa can grow fine near the substrate and incorporate bits and pieces into its flesh but zoas may not love it so much. Some hobbyists use substrate as a deterrent and make islands of zoas in the substrate to prevent them from extending their mat throughout their aquascape and encroaching on other corals.

Zoas as they grow will form an encrusting mat that will eventually cover the rocks if the colony is healthy and happy. That might bring up concerns of coral aggression with nearby corals. Zoas are not particularly aggressive so this is less of an issue, but everything on the reef is trying to battle for real estate at the end of the day, so it is something to consider.

![]() Feeding

Feeding

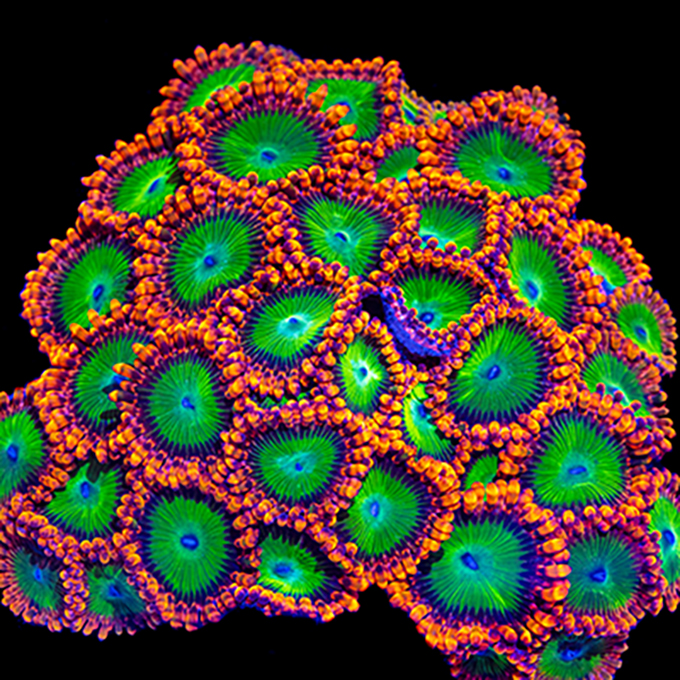

When it comes to nutrition, I think zoas benefit from regular feeding. They are not the most active feeders in the world and rely in large part on photosynthesis for their nutritional needs. The longer I am in the hobby the more aggressively I want to feed all my corals, and zoas are no different.

We try to feed a blend of small frozen foods such as the fines from mysis shrimp, cyclops plankton, and frozen rotifers. We have also tried feeding a variety of powdered dry plankton. Your mileage may vary depending on the species of zoa you have and also how you are doing the feeding.

As I mentioned they are not nearly as good a feeder as palythoa so they might not be able to grab chunks of food out of the water. I try to turn the pumps off and then give them a good dusting of food and let them sit for about 10 min before restarting the pumps.

![]() Chemistry

Chemistry

As far as chemistry goes, you do not have to worry about calcium, alkalinity, or magnesium as much as you would for delicate stony corals. You will want to keep those more or less consistent with natural sea water levels, but they are secondary to nitrate and phosphate.

Phosphate and Nitrate are great general measurements of water cleanliness. They show up mainly in the food we provide the tank but decaying plant and animal matter in the aquarium can also elevate their levels in the water. Zoas tend to do better in tanks that are not TOO clean. We generally shoot for about 10-20ppm nitrate and .05 to .1ppm phosphate.

If these levels get too high you may run into problems. For example if Nitrate levels get too high corals may react negatively by taking on drab coloration or suddenly dying back in extreme cases. If Phosphate levels are too high, it may feed into an unwanted algae bloom or spur on the growth of other undesirable organisms that can stifle the growth of corals.

Equally bad is if the water is completely stripped of phosphate and nitrate. For a short period there was a push in the hobby to have near zero levels of nitrate and phosphate. This is done through techniques like carbon dosing or GFO which can aggressively bring those numbers down. Ultra low nutrient levels though come with their own sets of issues. There is such a thing as too clean and I would argue the problems caused by near zero nutrient levels are much worse than those caused by an abundance of nitrate and phosphate.

Corals require some level of nitrate and phosphate available to them. When starved out, the zoas shrink down and don’t open very well. After that there is a risk for blooms of unwanted organisms such as brown dinoflagellates that thrive in ultra low nutrient conditions. I would rather see Nitrate and Phosphate levels on the high side than barely detectable because we have kept them in systems with very high nutrient with little to no difficulties.

That should give you a little bit of background on the chemical parameters to keep an eye on.

![]() Aquaculture

Aquaculture

So now that we have gone over the care requirements for Zoas, let’s talk about their prospects for aquaculture and long-term farming. In short, Zoas are an ideal choice for aquaculture.

First off, the color variation is nearly limitless. It is theoretically possible to have a commercially viable farm that only specializes on strains of Zoanthus because that could mean hundreds of lines and seemingly more and more varieties are introduced into the trade to bring into the collection.

Second, they are a fast growing coral that can be very easily propagated and heal well from cutting and gluing.

Third, many of the problems associated with Zoas come from wild colonies that are recently imported such as a long list of potential pests. A zoa grown in captivity is much less likely to have those kinds of problems.

![]() Pests and Diseases

Pests and Diseases

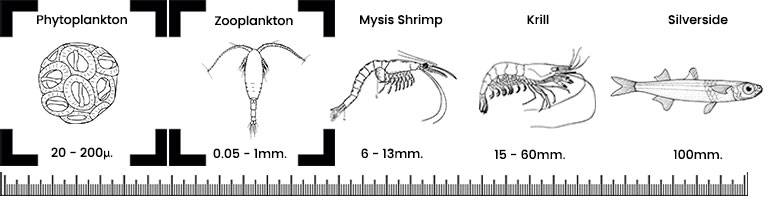

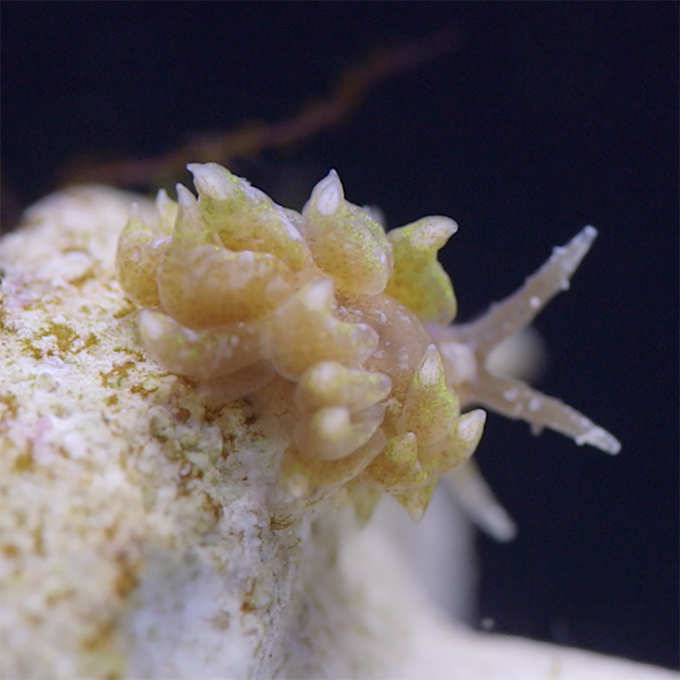

Zoanthid-eating Nudibranch

On the topic of pests, there are a plethora that can make life for zoas difficult. For a coral that is known for toxicity, there is no shortage of critters looking to make a meal out of them or at the very least harass them to the point they stop growing.

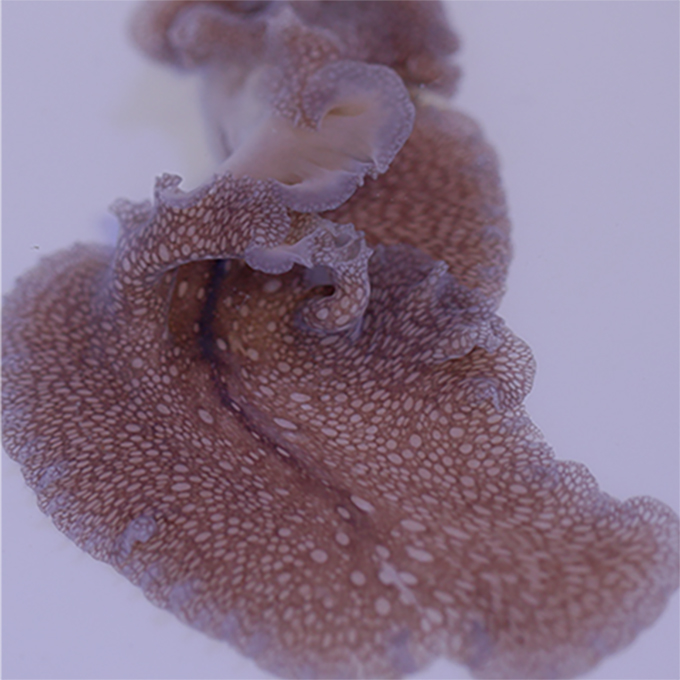

Starting with diseases, one of the more common diseases that effects Zoas is Zoa Pox. Zoa Pox looks like white pimples on the surface of the zoa mat.

The list of sea critters that can also annoy or cause damage to Zoanthids is a little extensive. First we have sea spiders, that latch onto zoanthids like face huggers from "Aliens".

Next, we have zoanthid-eating nudibranchs that can actually start to take on the appearance of the Zoas they are consuming. So often times, you will be able to see them if you make the colony close up. If you are left with some polyps that refuse to close, that means they aren't polyps at all, they are the nudibranchs.

There are also certain types of snails that would love to make a meal out of Zoanthids, called sundial snails, as well as really large flatworms. Those aren't incredibly common, but every now and then you do see flatworms hanging out on the faces of zoanthids.

large flatworm

There are also some microfauna-type crustaceans that don't exactly eat Zoas, but they like to build their mucus nest tunnels right up against the flesh of a Zoa, and that nest accumulates detritus which then stops the growth of the Zoanthus colony.

And last but not least there's crabs and fish that enjoy pestering and eating zoanthids. Fish are a strange one because, there's the obvious non-reef safe fish like the Butterflies and Angels that just nibble at these things, but I've seen Tangs and Foxfaces make a meal out of them on occasion and it's usually when it is a newly introduced frag that has maybe one or two polyps on it. For whatever reason, Tangs and Foxfaces (which would normally never touch Zoanthids) get very curious if it's a single polyp.

Mucus Tunnel

These are all things to consider when it comes to pests and diseases. Luckily, Zoanthus can be dipped by almost anything and come out looking much better. We do lots of preventative dips that are iodine-based for disease, we do dips that are pine oil-based for some of these pests, and in certain situations we can also do freshwater dips. So don't worry, all of these things can be dealt with.

![]() Conclusion

Conclusion

Alright, that about does it for this overview of zoanthus and their care requirements. Hopefully this was helpful for those looking to try them for the first time. If you would like to perhaps purchase Zoas for your home aquarium, I invite you to visit our Zoanthid page on this website and see what we have in stock. We are always on the lookout for new and interesting color morphs of this coral to add to our collection, and hopefully yours as well.

Until next time, happy reefing.